Fr Peter Beck presided and Fr Bosco Peters (liturgy.co.nz) preached. The Gospel reading was taken from Luke 13:1-9.

Read on for the sermon and a video of the service (and a cartoon).

Video

Sermon

This week, Helen and I walked to the mosque and stood outside in prayerful silence, remembering the 51 people who were praying peacefully and then killed in the terrorist attack there, we prayed for the more than 40 wounded, and the lives of so, so many changed for ever by a single, evil man. Daily, we watch unbelievable atrocities against people in Ukraine - again the result of one nefarious megalomaniac.

And then today, we just listened to people reporting to Jesus how Pilate has slaughtered some pilgrims who were sacrificing in the temple and then mixed their blood with that of their sacrifices. The group talking to Jesus also tell another story of a tower at Siloam collapsing and killing eighteen people.

Jesus has the perfect setting for a masterclass philosophy lecture in what is called theodicy - how does an all powerful, all-good God allow suffering to happen? Is it the karma that people so often so glibly talk about? Or is it brushed off with, “everything happens for a reason”? Do these people suffer because they are being punished for being bad, for being sinful? You cannot have faith in God for the long haul without grappling with why do bad things happen to good people.

What does Jesus do: Instead of Jesus giving a philosophy lecture to satisfy our head: you know the Siloam story is the result of living in a consistent universe - where the very solidity of stones needed to build a tower end up injuring innocent humans. And the Pilate story is the result of humans having free will.

No. Instead of addressing our head - Jesus addresses our heart. He says repent: Change your way of thinking; change your way of viewing things; change your way of living.

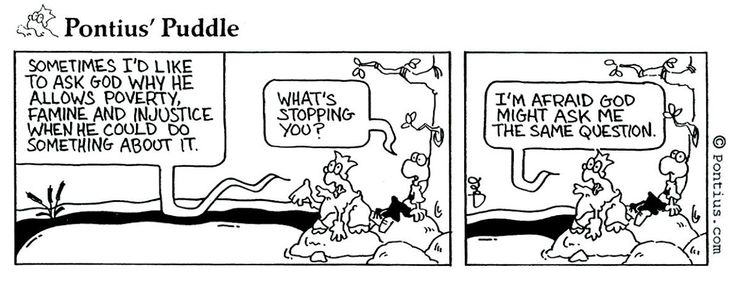

How do people become unsettled enough so that we change? One way we might not immediately think of is through humour. Every day in the newspaper, there’s a political cartoon trying to unsettle us into changing the way we think, the way we view things, the way we live. Such cartoons often poke the borax at powerful people. This stands in the tradition of the jester who pointedly, with humour speaks truth to power. How far you go with humour is always a fine line; you can raise the ire of very powerful people; humour can be dangerous.

At a time when we have become used to having slow-witted clowns lead some of the most powerful nations in the world, it is inspiring and refreshing to have Volodymyr Zelensky as President of Ukraine. Here is a highly intelligent, principled man, a law graduate, who - akin to John Cleese of Monty Python - switched from law to acting and humour. Zelensky had a television series called Servant of the People in which his character was a lovable secondary school teacher who was fed up with corrupt politicians and in the series he accidentally becomes president.

Life imitated art and he is now bringing his intelligence, his moral principles, and his dry humour to being the real president of Ukraine. And doing so at the time of its greatest need. When the United States of America offered to evacuate him so he could lead the country in safety, his droll reply was: “The fight is here. I need ammunition, not a ride” When Russia spread misinformation that Zelensky had fled Kyiv, with wry whimsy he mocked them by posting a video online from the streets of that city.

He issued a statement to Ukrainians, that if you capture a Russian tank, you don’t need to declare that as income for the tax department. And he encouraged people to change and move road signs so that the Russians would get lost and confused.

He is treating Putin and the Russian invaders a lot like an intelligent comedian would respond to an annoying heckler in the crowd.

Zelenski is the first Jewish head of state of any country other than Israel. He understands suffering; he understands faith in God; and he understands the Jewish tradition of responding to suffering with powerful, dry humour.

Jesus stands in this Jewish Jester tradition, speaking truth to power in compelling, memorable images and stories. God’s reign, says Jesus, is like a woman mixing flour - have you ever checked how much flour Jesus mentions?

THAT’S why it funny; that’s why it’s memorable: the woman in Jesus’ story is baking 60 loaves of bread!

Jesus tells the story of a woman who loses a coin. She turns her house upside down searching for it, and when she does find it, she pays for the whole street to have a party. What about the carpenter joke: you’ve got a plank of wood stuck in your eye, and you’re trying to get a speck of sawdust out of someone else’s eye?! Or Jesus talks about people who end up swallowing a camel, but will strain out a gnat with a fine sieve. You’re picturing the camel shape poking out either side of this person’s body.

Even Jesus’ actions stand in this Jester approach - in 3 weeks time, we celebrate Palm Sunday. At that time of year Pontius Pilate marches on Jerusalem from his residence at Caesarea on the coast in order to - as he would say - keep the peace, to keep Roman control at passover. Dressed in dramatic robes and iron protection, mounted on his armoured horse, Pilate leads his soldiers with the best military technology of his day - he’s coming from the West to Jerusalem.

And what does Jesus do at the same time? He mockingly mimics Pilate. Jesus hops, unarmed, onto a donkey, and with a motley band of peasant followers, he mirrors what everyone knows Pilate is doing on the other side of the city. Pilate is entering Jerusalem with all military might on the West and Jesus the Jewish Jester is parodying Pilate by entering on the East.

Today, here, at this Mass, Jesus this Jewish Jester, instead of giving a philosophy lecture in response to suffering speaks to our heart by yet again telling a memorable humorous story. An expert in Middle Eastern humour writes about this story, “Jesus’ original peasant audience undoubtedly roared with laughter.” In Aramaic, today’s fig tree story is even better, with puns that are lost in translation.

A wealthy, absentee landowner is inspecting his property. Usually, in Luke, these sort of people get a really hard time - but this man has been surprisingly patient.

They’ve been following the rules found in Leviticus: you plant a fig tree and let it grow for three years; the next three years it will produce some fruit - but you mustn’t harvest this during these years; just leave it. Then there’s a year when you can offer the fruit to God, and after that, you can start harvesting. So, in today’s story, the landowner has been patiently checking this tree for nine years. Nothing. No fruit. It’s a waste of good space. Get rid of it. Plant another tree or vine.

But the gardener, who is getting nothing out of this tree, clearly loves this tree. That’s unconditional love. I’m nuts about this tree - give me a chance, I’ll aerate the soil, and I’ll add the best fertiliser. I really think it will bear fruit. Jesus' response to suffering is not philosophy. Jesus points to the heart of reality, the one we call God, and Jesus says this God is for us, not against us.

The tower, the quakes, the shooting, the war, the evil of individuals - this is not God getting anyone back. This God is nuts about us.

When Helen and I were away, biking a trail alongside the Clutha River, we came across a nineteenth century grave - a man had drowned in that river, and, so the story goes, not knowing his name, he was buried with the wooden plaque which read: “Somebody’s darling lies buried here”. Each person is someone’s darling. Each person is God’s darling. God is nuts about each of us.

Even when you and I are fruitless - there is a time to aerate the soil, and add the best fertiliser. Lent is that time. Time to pray, to pick up the psalms, for example - if you don’t already do so - and find there: anger, joy, depression, thankfulness, lament.

The world preaches about a relentless, toxic positivity: you can be happy, be happy, be happy. The followers of Jesus know that the goal of life is not happiness, but union with God. Happiness can be a nice byproduct. Life is a mixture of good and evil, joy and tragedy, of rage and gratitude; the psalms express this so well.

When you grieve, you honour what is lost. When you are angry, you acknowledge this matters. Grief and gratefulness, unhappiness and hopefulness are intertwined, all valid parts of life, aspects of genuine reality.

The rich and powerful promote the false teaching of pernicious positivity - because then unhappiness is your fault rather than that of structural inequity, rather than systemic injustice.

Lent isn’t just a self-improvement programme. Payer and contemplation isn’t just about helping me cope with life’s difficulties. Fasting in Lent isn’t just a dieting course. Lent and Easter - resurrection and death challenges individualism, challenges the focus on me and my needs. Lent is also about upending systems of injustice, not just about personal piety.

Ash Wednesday’s Isaiah describes well the fast of Lent: God says: "this is the fast that I choose: to loose the bonds of injustice, to undo the thongs of the yoke, to let the oppressed go free, and to break every yoke.

God’s fast is to share your bread with the hungry, and bring the homeless poor into your house; when you see the naked, to cover them.”

God’s response to suffering, to evil, isn’t a philosophy lecture.

There’s a great cartoon - to conclude by returning to the Jester again - there’s a great cartoon where one person says to another: “Sometimes I’d like to ask God why he allows poverty famine and injustice when he could do something about it.” What’s stopping you - says the other person. To which the first person replies: I’m afraid God might ask me the same question.